Contradictions Confirm Need for Socialist Change

India is a testing area for a rightwing nationalist government under the BJP’s Narendra Modi ⬤ Its failure to bring social progress or even contain the Covid-19 crisis, in the context of rising global tensions, strengthens all pre-existing contradictions.

India is not just a country. It is a continent with over 1,3 billion inhabitants. It is a testing area for a rightwing nationalist government under Narendra Modi. The failure of the rightwing BJP-government to bring social progress or even contain the Covid-19 crisis, in the context of rising global tensions, strengthens all pre-existing contradictions.

Health crisis

In a country full of inequality, where the 9 richest persons have as much wealth as the poorest half, the Covid-19 crisis has devastating consequences.

In Assam, in the North East of India, about a hundred Covid-patients escaped from their care center to occupy a national highway in 16 July to protest. They share a single room with 10 or 12 persons in unhygienic conditions and with a lack of food. Those who don’t die from Covid-19 might as well die from other diseases or just hunger. At the same time, Shankar Kurade, a rich man in Pune, got himself a gold mouth mask produced for a price of 3.500 euro. The man added he was not sure how effective the mask would be…

In the whole of India over 1 million people have been contaminated with Covid-19. The death toll mounted to over 25.000 with the rate currently increasing. There are cases in the center of India, such as Maharashtra and Mumbai, the north Delhi and Gujarat and the south in Tamil Nadu. The rhythm is very different from state to state, but the virus is present in the whole country and the terrible conditions of the health sector make the situation worse.

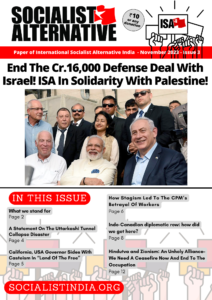

The response of the government came late. When the first cases of Covid-19 in China appeared, Modi was too busy with other things. He was continuing his Hindu-chauvinist policies in India itself, while at the same time propping up his international profile. In January Brazilian president Bolsonaro made a visit to India, in February US president Trump followed. Being promised a meeting with 1 million present in Gujarat, Trump couldn’t refuse the invitation. In India itself the campaigns against Muslims were stepped up, partly as an element of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) strategy for the local elections in Delhi on 7 February. The BJP has not been able to break the power of the anti-corruption party Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) in Delhi and frustration has been growing. After the elections more than 50 people died in communal violence in the capital.

Government pays no attention to healthcare

India was not well prepared for the health crisis. When it started, India was still exporting protection material (PPE) and other health supplies. When the number of cases started to increase, the government asked the people to go onto their balconies to applaud and to pound pots and pans to support the health workers. The government however didn’t provide any extra public investment in health care. When at the end of March, the government suddenly announced a complete lockdown, the country and its millions of informal workers were absolutely unprepared. There were dire consequences as a shortage of food developed in Delhi and millions of migrant workers tried to get home after they lost their work in the big cities. The brutal face of Indian capitalism was shown in the violent repression against ordinary workers and poor people.

The public budget for health is only 1,3% of India’s GDP. In 2018 Modi promised a reform of the health system to provide the 100 million poorest families access. The results are very limited and the reform leads to a lot of corruption, without improving access to the health infrastructure. The aim is to get more people on a health insurance to grow the market for the private health sector. Since 2005, the only growth in capacity was in the private sector. Already 58% of the hospitals are in private hands.

Modi and the BJP-government are weakened by the Covid-19 crisis but luckily for them the opposition of Congress is too weak to make use of this. Modi was first elected in 2014 with the hope he would be a ‘strong’ man bringing economic progress for the whole population. He hasn’t delivered and had to make use of a more radical Hindu-chauvinist campaign against Muslims coupled with appeals to ‘Akhand Bharat’ — a greater ‘undivided’ India to get re-elected in 2019. Nationalist and chauvinist policies are based on division, but the virus hits everyone. Modi used his Hindu-chauvinist rhetoric when he announced from the city of Varanasi that he would wage a war against the virus and would win in 21 days. A few months later it has become clear that chauvinist rhetoric is not a very efficient vaccine against Covid-19.

The lock-down was eased while the health crisis was still increasing. This was not for health reasons, it was about the economy.

To give an indication of the economic impact: the demand for electricity declined by almost 30% in April. The demand for fuel fell dramatically: oil refineries halved their production. The big automobile company Maruti didn’t produce a single car in April. Bajaj Motors, a company selling two and three-wheelers, saw a drop in sales of 80% in April. The government organized ‘Unlock 1’ to get production back on its feet. The economic package announced by the government was aimed at providing some basic infrastructure for patients, but mainly at stimulus measures for companies. The government claims the unemployment has already fallen back to pre-Covid level, but at the same time figures for electricity consumption show a decrease of almost 10% in June 2020 compared to 2019.

As part of the stimulus of the economy, the government wants to continue the attacks on workers. The privatization of a part of the power sector is on the agenda. Attacks on labor legislation have again been stepped up in many states. This is not a new thing: the huge general strike in January 2020, with over 250 million participants, was aimed against privatizations and the counter reforms of labor legislation. Under pressure of the mass movement against the 2019 Citizenship Law, the strike also took up this political issue. This is important: in general, the Indian unions try to limit strikes to direct economic issues. The restarting of the economy is now used to strengthen the attacks on the workers. In some states there is discussion on extending the working day from eight to twelve hours, or about suspending the minimum wage and making it easier to sack workers. This has already led to a strike on 3 July and continuing actions, for example in the coal sector.

BJP government built on contradictions and division

The right-wing Hindu-nationalist BJP-government is built on contradictions and communal division. The hopes for progress that the poor masses had have not materialized, and in a context of the economic slowdown which had started before Covid-19, this will not get better. All that has been left for the BJP in the 2019 election campaign was to use an even more nationalist approach based on some of the historical demands of the Hindutva combined with a polarizing approach aimed at certain voters. BJP provocations always serve its own electoral agenda. This includes Kashmir, the Citizenship Amendment Act or the longtime campaign to build a new temple in Ayodhya, a project due to start any moment now.

The predecessors of the BJP had a strong base among Hindus in Kashmir where they strongly opposed any step towards independence. The first national BJP-campaign led by Modi in the early 1990s was a long march to Kashmir to confirm India’s ‘unity and indivisibility’ in a ceremony in Srinagar. The campaign failed in part, the march never really got in Srinagar, but it indicates the importance of the issue both for Modi and the BJP.

When the BJP came to power in 1998 it immediately held nuclear tests. At the same time Pakistan had a military government under Musharraf, with the army having taken power to defend its military and economic interests. Musharraf played an active role in the army in Kashmir. The tensions between BJP-led India and the military regime of Musharraf in Pakistan led to the serious danger of an escalation between the two new nuclear powers. Both needed the tension: the BJP to show the ‘greatness’ of India, Musharraf to prove the importance of the army. But such attempts to demonstrate strength in ways that could possibly kill millions of people are usually a result of the failure to provide the masses with a better future. Instead, they are offered a ‘dream’ of a big and great country. An open war was avoided in 1998–99, but the issue of Kashmir has remained on the agenda.

Kashmir was again a central theme in the election campaign of Modi in 2019. In February 2019 a bomb exploded in Pulwama in Indian Occupied Kashmir (IOK). In the north of India students from Kashmiri origin had to flee and saw their access to higher education blocked. There were death threats against people who helped Kashmiri. In Jammu, part of Jammu Kashmir, tensions rose with violence against Kashmiri. This was used by the BJP to stir up anti-Muslim feelings and to win the votes of Hindus.

After the election, the Modi-government immediately abolished article 370A of the constitution that granted a special status for Kashmir. This special status was part of the agreement between the Maharaja of Kashmir and the Indian government during partition between India and Pakistan in 1947. Hindu-chauvinists have been demanding the end of this special status for many years. Following a very nationalist election campaign, Modi saw this as an opportunity to lean on the growing anti-Kashmiri feelings in the north of India and the civil war-weariness of people in Kashmir. Abolishing article 370A of the constitution opens the possibility for non-Kashmiri persons to buy land in the mountain state and thus change the demographics. At the same time Jammu Kashmir was split into two union territories. “Hard decisions need to be taken to change the situation,” was how Minister of Interior Affairs Amit Shah described the measures.

BJP whips up Hindu nationalism

A second controversial measure taken by the government was especially aimed at the population of the so called cow belt, the states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh where the sacred character of the cow is extremely important in the local version of Hinduism. For decades the Hindu-nationalists have campaigned to get a Hindu temple built in the town of Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh. They claim a temple was destroyed there to build a mosque. Campaigning on this issue was an important element that helped to bring the BJP to power in Uttar Pradesh in the early 1990s. It led to violent attacks and mobs destroying the mosque in 1992, under the leadership of BJP-leaders. This was followed by violence in different parts of India, killing over 2000 persons.

Now the BJP-government has obtained permission from the high court to start building a Ram temple in Ayodhya, with Modi planning to attend the religious ceremony to launch the construction. Former BJP-leader Advani once said: “Ram is not just a religious icon. He is also the symbol of the Indian ethos, culture and unity. He is the personification of our concept of cultural nationalism.” The start of the building of a Ram temple will strengthen the BJP-profile in the cow belt, although at the same time it puts no food on the tables of the poor masses.

Thirdly, and most disputed in India itself, were the measures around the Citizens Amendment Act (CAA). The central government proposed a National Population Register (NPR) on the basis of a National Register of Citizens (NRC), as part of an attempt to determine who can be seen as an Indian citizen and who not. The Citizens Amendment Act added that non-Muslims from four neighboring countries could become Indian citizens. Exempting Muslims shows the real issue at stake for the BJP: creating division.

In the North East of India, this issue has long been part of the electoral strategy of the BJP. Now, even in West Bengal this is having an effect with the BJP making its first breakthroughs. Although campaigning here on Ayodhya is less effective, because religious differences with less attention paid to Ram as a deity is combined with a stronger history of the left. The failure of the left however, has created an inroad for the BJP. Resistance against immigrants from Bangladesh is a crucial part of this. A first test with the measures in the state of Assam showed that more than 1 million people were ‘not wanted’. Senior BJP minister Amit Shah had already in 2018 talked about refugees from Bangladesh as ‘termites’.

While these measures are useful for the BJP in the north east, in different parts of the country their attacks are aimed at other populations. By refusing Sri Lankan Tamils, a majority of them Hindus, the right to be Indian citizens shows the contempt of the BJP towards the masses of Tamil Nadu and the divisions between north and south India.

In December and January hundreds of thousands protested against these measures. The BJP reacted with increasing violence. In February more than 50 died in riots in Delhi. This violence seemed well prepared and had reminiscences of the 2002 Gujarat violence, when after an incident when Hindu pilgrims returning from Ayodhya were attacked, a brutal campaign was organised against Muslims. Over 200 mosques were burnt, 150.000 people left their homes and more than 1000 died. Then chief minister of Gujarat was the present prime minister Modi. The Gujarat-model of violence with the BJP seen as accomplice is spreading to other parts of the country.

Economic failure

The slowdown of the Indian economy started before Covid-19, but is, of course, strengthened by the virus. The economic policies of the BJP in the past years were aimed at liberalization and attracting foreign investment, even when the party continued to talk about economic nationalism and even of ‘Gandhian socialism’. In the past years the living standards of the masses have not improved, being continuously under pressure from inflation.

India’s top 1% of the population hold 42,5% of its national wealth, 4 times more than the bottom 70% of 953 million people. Research by the French economists Piketty and Chancel showed that in the late 1930s the top 1% of earners captured 21% of the total income, this dropped to 6% in the early 1980s and has since then grown back to 22%.

Neoliberal policies have been used by both Congress and the BJP, and are presented as the only possibility. This has an effect on consciousness. But it doesn’t mean that there is no protest. On the contrary: the general strike on 8 January of this year was the biggest ever. With over 250 million participants, more people went on strike than the 229 million who voted for the BJP in May 2019.

That is important: it shows that the nationalist rightwing can win elections, but also that resistance against it is not limited to the electoral process. With 250 million strikers the working class showed its huge potential force. If this force was to be used on the political terrain, it would be big problem for Modi, but this requires an offensive approach and program.

In its response to the crisis the Indian government is laying the basis for further and continuing class struggle. The stimulus package is mainly aimed at giving presents to the companies and the private sector. Concessions for the poor are very limited, while at the same time new attacks on workers are being prepared or introduced. All contradictions are being strengthened and will be expressed in different ways.

How did the BJP get here?

The BJP has a long history as a small party, built consciously from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteer Organisation (RSS) militias. Several factors made the growth of the BJP possible.

First of all, the policies of the Congress party are based on a neoliberal program of liberalizations and attacks on the workers, leading to more inequality and social unrest. Congress is seen as a party of the new rich and of corrupt politicians. People appalled by Congress can often look towards the BJP to find an alternative, even when the BJP stands for the same neoliberal policies.

Secondly, in the rise of the BJP there is, of course, the element of Hindu-nationalism. While this was always present in the predecessors of the BJP, Hindu-nationalism really became mainstream in the 1980s under Indira Gandhi. After three years in opposition, Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980. Her government had to play up the nationalist card. This was not new in the ‘secular’ Congress party, but Indira Gandhi needed a more chauvinist profile after the failure to implement social reforms in the 1970s. In the 1980s she went from temple to temple as a sort of Hindu-goddess and attacked the Sikhs in Punjab, with the deadly attack on the golden temple of Amritsar in 1984 as the ‘highlight’. Congress gained electorally from this, but it also made Hindu-nationalism mainstream. In the longer run, the BJP has profited from this. Especially when it becomes the only electoral theme, the ‘best’ Hindu-nationalist can win. Congress at some point thought it already owned the Hindu-votes and could buy the votes of other communities. Trying to build a stronger base on a communal basis instead of social progress, led to growing disillusions in Congress and opened the way for the BJP.

After the fall of the Stalinist dictatorships in Russia and eastern Europe the potential danger posed by the ‘communist’ parties was reduced. Even before that, the mistaken two-stage theory by which they argued that first capitalist development was needed before socialist change could be on the agenda, meant that the communist parties tail-ended bourgeois politicians and their policies. At one time, this even included forming alliances with the BJP ‘in defense of democracy’. The ideologically weak CP’s were even weaker after the fall of Stalinism. This reduced the danger of a mass movement putting socialist change on the agenda, allowing the ruling classes to go further with neoliberal policies and an openly reactionary government led by the BJP, first under Vajpayee in 1998 and now under Modi after 2014. The potential of the workers and poor masses, of which the strong electoral positions of the CP’s were an expression, has not disappeared. But a potential has to be used, otherwise it will need to find other expressions.

Workers movement must go onto the offensive

The history and strength of the BJP today is the result of all the contradictions of Indian capitalism, which in turn lead to no new complications. “The bourgeoisie in countries that have come late to the road of capitalist development, is politically sterile, cowardly, talentless and rotten through and through with chauvinism”, Trotsky said about the Balkans before WW1. The uneven and combined development of the economy creates new contradictions. Failure on the social-economic field means the chauvinist and nationalist elements tend to become more important.

While not hesitating to formulate strong rhetoric against the governments of Pakistan or China, a full war would be catastrophic for the BJP government because of the economical and human impact such a war would have. The BJP claims it wants the economic self-reliance of India, using elements of protectionism in the international situation and linking up with rightwing politicians like Trump and Bolosonaro, but at the same time it tries to use the China-US tensions to attract foreign investment from the US and Europe and at the same time to lower its own trade deficit with China. The Indian government furthermore hopes to strengthen its geopolitical regional position on the basis of the weaknesses of China. But of course, India is also weakened by the present crisis.

The fact remains that India is a huge country with an economy that is not very developed, with failing infrastructure and huge inequality leading to tensions. There are huge social tensions around the labor laws, but also on issues like division and discrimination on a caste basis with big movements against violence on Dalits and untouchables, or the big protests against sexist violence. The BJP always choses the side of the rich and powerful, even when it needs a broader image for electoral reasons. The BJP uses its version of ‘national unity’ to oppose struggle against oppression, whether on a caste basis, class or national oppression with a national question becoming more difficult instead of being resolved.

There is the danger of communal violence and the threat of increased regional tensions. This was shown in the border incidents between China and India in Ladakh in June. The only force capable of stopping an escalation of violence and poverty, is the working class.

The working class has a big potential. The general strikes, the latest in January this year, have shown this. There is an urgent need for a serious and coordinated strategy in the fight against Modi and his pro-big business policies. In this strategy offensive demands are essential, linking the economic struggle with the fight against all forms of oppression and attacks on democratic rights. These need to be part of the struggle for socialist change.

It is only the working class that can show a way out of the growing nightmare and contradictions in India. The working class in India today is a lot stronger than the Russian working class in 1917. Over one third of the Indian population lives in urban areas today. The old Stalinist idea that the working class is not strong enough, can no longer seriously be upheld.

More than 70 years after independence and the partition of India, it is clear that India will not develop to a strong and stable capitalist power. It has known an important capitalist development. This however has not brought stability in India itself, but just new complications and contradictions. In the struggle for socialist change the working class has to play a key role, but also needs to defend change for the farmers and land reforms. It also needs to address the specific forms of oppression that more and more lead to big protest movements, whether based on caste, women rights, LGBTQI-rights and so on. Marxists do not contrapose struggle against specific oppression to workers struggle for socialism, but see an important and crucial potential in it to bring forward the struggle for socialist change.

The danger of more communal violence and regional tensions should not be underestimated, but the potential of the young Indian working class and its allies amongst the oppressed masses should neither be underestimated. Using the available wealth, resources and technological knowledge for the benefit of the majority of the population is the only way to seriously improve the living standards of millions of Indians. This means fighting for a socialist society in which the key sectors of the economy are put in public hands so that democratic planning becomes possible.